What happens when a novelist receives a sneak-preview bottle of a brand-new 10-year-old bourbon? A whiskey-flavored outpouring of memories, both happy and haunting

“THIS,” MY FATHER SAID, pointing to the bottle of Jack Daniel’s on the table in front of him, “is sour mash whiskey.”

That bottle only came out of the cupboard at holidays or when someone died. He drank his whiskey in an Old-Fashioned glass, filled to the brim with ice. I loved the ritual of it—watching my father crack the ice cubes out of the frosty silver tray, the way the amber liquid tumbled over them, sending the ice tinkling, my father’s sigh after he took the first sip. As James Joyce said and my father would surely agree: “The light music of whiskey falling into a glass—an agreeable interlude.”

What I did not love was that amber liquid itself. Iodine, I thought when I tried it. I was a teenager, and like many young girls I liked sweet drinks—sloe gin fizzes, fruity daiquiris—or drinks with provocative names—Sex On the Beach, Slippery Nipple. In my 20s I took a shine to Chablis, in my 30s buttery Chardonnay. But here I am now, well into middle age, and it is whiskey that I prefer, poured over one giant ice cube.

Whiskey is any spirit distilled from fermented grain mash—barley, corn, rye—and then aged in wooden barrels. All bourbons are whiskey, but not all whiskeys are bourbon, my father taught me. Bourbon is actually governed by bourbon laws, which were set in the Bottle in Bond Act of 1897 to keep distillers from diluting or tampering with it. Before that Act, bourbon was bitter and, well, bad. The bourbon we drink today must be produced in America and made from 51 % corn.

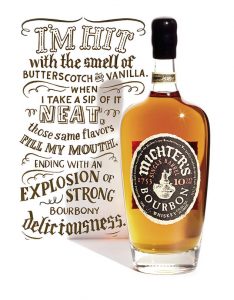

The Michter’s 10 Year Single Barrel Bourbon that arrives on my doorstep, courtesy of my editor at The Wall Street Journal, has been patiently aged in charred new American oak barrels, which give this bourbon its deep amber hue. This bottling was originally set for release at the beginning of this year, but Michter’s Master Distiller Willie Pratt held it back for a bit more aging. Nicknamed “Dr. No” by the Michter’s sales force due to his frequent refusal to release whiskeys before he believes they have sufficiently matured, Mr. Pratt is a stickler for quality. “I wanted them to be just right,” he said of both Michter’s 10 Year Single Barrel Bourbon and 20 Year Single Barrel Bourbon. As a result of his perfectionism, the bottle on my table won’t be for sale until December; receiving it in November gives me a slight thrill, as if I’m doing something illicit. I’ll be one of the first people to taste it.

I love firsts: first dates, first kisses, first sips. On my first sip of Michter’s 10 Year Single Barrel, I bend my nose toward it, and I’m hit with the smell of butterscotch and vanilla. When I try it neat, those same flavors fill my mouth, ending with an explosion of strong bourbony deliciousness. I taste it next with a splash of water, which dulls the explosion more than I like. Best of all, I pour some over one giant ice cube, and have a perfect glass of bourbon to savor for much of a chilly November afternoon.

Michter’s in hand, I look out at the sidewalk covered in autumn leaves and remember my first tastes of whiskey. That long ago sip of my father’s Jack Daniel’s—iodine—yes. Then a decade or so later, with my first husband, a whiskey drinker. I was in my Chardonnay phase. But one cold December night, after we were mugged on a Brooklyn street corner, we went into our apartment, trembling, and he poured us each a tumbler of whiskey. I remember how my hand shook as I lifted that glass, how harsh and strong and somehow right the whiskey tasted. It was just what I needed to still my fear, and when I think of that night—the empty street, the wild-eyed mugger wielding a knife—I somehow always land on the comfort of whiskey neat.

The Michter’s mellows as the ice melts and the afternoon light fades. I find myself remembering a long ago trip to the Isle of Skye when it rained every day, a cold hard, relentless rain that kept my sweaters and pants and all of me damp, the kind of damp that slowly settles into your bones and chills you thoroughly. After getting caught in a particularly big downpour, I found a pub with a big fire roaring in the hearth and tried unsuccessfully to warm myself by it. The bartender saw me, wet and shivering, and slid a glass of whisky (as it’s spelled in Scotland) toward me. What I didn’t know then was that this was an Islay single-malt, a whisky known for its peatiness. All I knew was that when I took my first sip, it was like sipping smoke. A slow heat crept down my throat and into my gut, and for the first time in a week, I was warm.

“There is no bad whiskey,” Raymond Chandler claimed. “There are only some whiskeys that aren’t as good as others.” Sitting here over a second glass of this very, very good bourbon, the sky dark now, remembering all those first sips, I have to agree with him. No other drink has the ability to bring forth so many memories. That is why, now, I find myself thinking of my father in his red suspenders decorated with happy Santas, pouring his Christmas whiskey. But, as I said, it wasn’t just on holidays that he took that bottle out of the cupboard. On the hot June day my brother died suddenly, I stood at the front door, gazing into my parents’ kitchen, hoping ridiculously that there had been some mistake. When I saw my father at the table, a glass of whiskey in his hand, I knew that it was true.

Fifteen years later he took the bottle down after his own diagnosis of terminal lung cancer. Even though I had not yet acquired a taste for it, I drank a glass of whiskey with him that afternoon. It tasted harsh and bitter. But I drank every drop.

If you are a person who remembers firsts, you also remember lasts. The last time I shared a whiskey with that husband at the end of our marriage. The last time I saw my brother alive, grinning at a barbecue grill. The April morning I held my father’s hand for the last time. In his famous “If-by-whiskey” speech to the Mississippi legislature in 1953, state representative Noah “Soggy” Sweat said: “If when you say whiskey you mean the stimulating drink that puts the spring in the old gentleman’s step on a frosty, crispy morning; if you mean the drink which enables a man to magnify his joy, and his happiness, and to forget, if only for a little while, life’s great tragedies, and heartaches, and sorrows, then I stand by it.” I do too, Soggy. I do too.